The population of Sana'a, the capital city of Yemen, depends on deep wells that are usually dug to a maximum depth of 200m for their drinking water. The wells draw on a Cretaceous sandstone aquifer northeast and northwest of the city, with a third of the wells operated by the state-owned Sana'a Local Corporation for water supply and sanitation drilled to 800 to 1,100m. The combined output of the corporation's wells barely meets 35 per cent of needs of the city's growing population, which includes displaced people, asylum seekers, refugees and other newcomers.

Some houses receive public piped water delivery once every 40 days, while others do not receive piped water at all. Sana'a's population is thus supplied either by small, privately-owned networks, hundreds of mobile tankers or people's own private wells. As water quality has degenerated, privately owned kiosks that use filtration to purify poor-quality groundwater have spread in Sana'a and other towns. Many people rely on costly water provided by private wells supplying tankers. The operators of these tankers don't really consider appropriate cleaning, and so the quality of the water is questionable.

Despite the challenges with pumping due to a shortage of fuel and rising prices, private well owners are trying to capture the remains of the valuable groundwater resources before their neighbours do. Coupled with the on-going war, drought sees Yemen facing a major water crisis. The water table in Sana'a dropped 360m between the 1970s and 2012.

Although Sana'a's groundwater is probably the best water in Yemen, it is considered below acceptable standards for human consumption as water infrastructure has been damaged by warplanes and the sanitation workers went on strike because they didn't get their salary. These issues left plenty of garbage on the streets that led to contamination of drinking water supplies. Meanwhile, wastewater began to leak out into irrigation canals and contaminate drinking water supplies. Inadequate attention to groundwater pollution has directly affected the quality of Sana'a's drinking water supplies.

In Yemen, as a whole, it is estimated that about 14.5 million people don't have sustainable access to clean drinking water. Inadequate water supply in the country has contributed to the worst outbreak of cholera in human history. Over 1 million suspected cases of cholera have been reported in Yemen since April 27, 2017. Other waterborne diseases include a recent peak in diphtheria that reached 1,795 probable cases with 93 associated deaths and a case fatality rate (CFR) of 5.2 per cent by May 19, 2018.

Yemen's groundwater resources are under pressure as never before to meet not only drinking-water needs but also the demand from irrigation. Climate change, demographic change and conflict place an immense burden on professionals in the country. The urgency of the needs means that water-resource management is neglected, despite being absolutely essential for the future of Yemen's population.

Sana'a's groundwater resources are significantly depleted in many areas and acknowledged globally as one of the world's scarcest water supplies. Sana'a may be the first capital city in the world to run out of water. Looking forward, how can the country produce more food, raise farmer incomes and meet increasing water demands if there is less water available?

Clearly, there are several interrelated aspects contributing to the current water crisis in Sana'a specifically and Yemen in general, and the population has to innovate to find solutions. Future supply options include pumping desalinated water from the Red Sea over a distance of 250km, over 2,700m-high mountains into the capital, itself located at an altitude of 2,200m. However, the feasibility of this is questionable and the pumping cost would push the price of water up to US$10 per cubic metre. Other options to supply Sana'a from adjacent regions are fraught due to water rights.

Groundwater data is the critical foundation for water managers to both prevent problems and formulate solutions. Data is lacking in many of Yemen's groundwater basins. Even heavily used basins have no record of how much groundwater has been withdrawn, how much remains in the aquifers, or where it was pumped from? Nor are adequate data available on groundwater quality or aquifer characteristics. Furthermore, the cutbacks in water supplies are motivating groundwater users to drill new or deeper wells in increasing numbers, despite the fact that well owners don't know how their aquifer is doing and so cannot anticipate changes. There is lack of data on private wells, too.

Lack of groundwater data in Yemen is not the result of ignorance about its importance, but rather due to chronic underfunding and politics, exacerbated by the on-going conflict. The war has made it almost impossible to measure and manage groundwater development and secure its long-term sustainability.

Having just completed the online course on ‘Professional drilling management' led by Skat Foundation, UNICEF and the UN Development Programme Cap-Net, I have learned about the need to develop our knowledge in this regard. The course highlighted important immediate and long-term actions for Yemen:

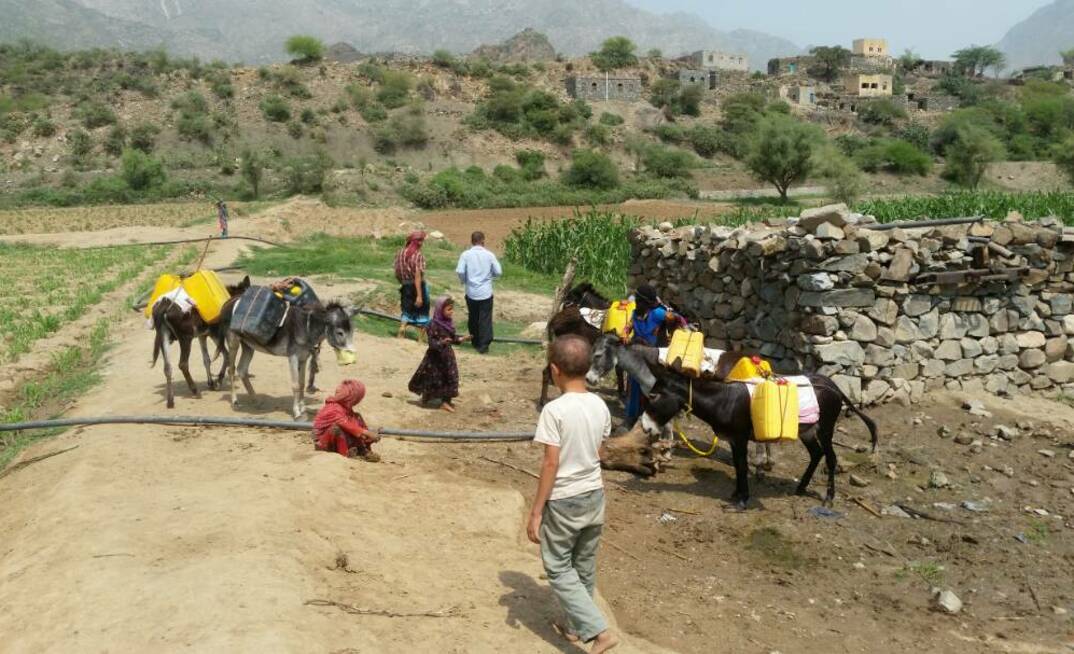

- Invest in building rain-water harvesting facilities in rural areas so the people do not have to walk miles to collect water;

- Find practical ways to better understand groundwater, regulate its extraction, introduce control mechanisms and engage with the local population to develop effective actions;

- Raise awareness within Yemen of the groundwater issues faced by the country;

- Build capacity of government, NGOs, consultants, policy makers and beneficiaries through training in groundwater management;

- Invest in re-building infrastructure along with improving water-resources management.

Muna Omar is an Ethiopian refugee, living and working in Sana'a, undertaking monitoring and evaluation of humanitarian programmes in the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), health and nutrition sectors such as a cholera-response project, and an executive assistant with a local NGO